Posted: July 11, 2020

Chart: EBHE

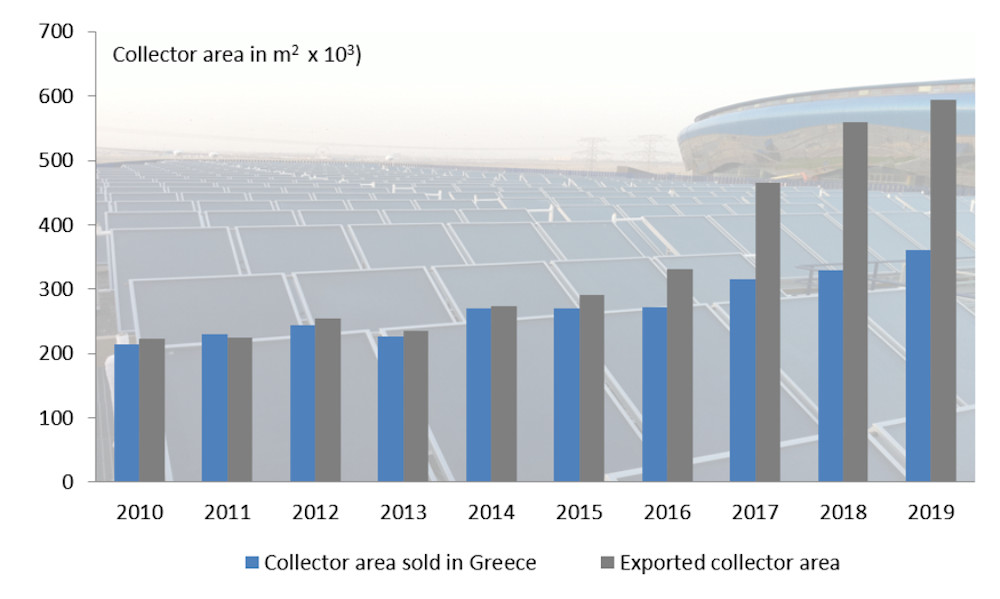

The Greek solar thermal industry is an export champion: The total collector area sold to customers abroad tripled from 200,000 m2 to 600,000 m2 in only 10 years (see chart). Greek manufacturers took advantage of opportunities around the world while demand for their cost-competitive and reliable products also grew at home. During the latest IEA SHC Solar Academy Webinar, held on 24 June, Dr Vassiliki Drosou, Solar Thermal Department Head at the Greek Centre for Renewable Energy Sources (CRES) and Solar Keymark Network Manager, explained to attendees which key factors contributed to this success story. A recording of the event and the presentations given at the webinar are available online.

In Greece, thermosiphon systems dominate solar thermal sales, providing 80 % to 90 % of the hot water demand of a family annually, because the southeast European country is blessed with sunshine all year round, even in the cold season. “Each one of our clients knows they have a well-performing system because they turn on the electric heater very few times a year,” Drosou said during per presentation.

Usually, these thermosiphon systems have 2 m2 to 4 m2 of collector area and a storage tank that can hold 150 to 300 litres. Most of them also use antifreeze liquids. They cost only one month’ worth of income, which makes them an easily affordable residential hot water system, and can be installed in under a day.

Greek flat plate collector manufacturers supply over 95 % of the national market. Strong branding means importers have little chance of getting their products to consumers.

Thermosiphon systems at the Bay hotel and resort in Zakynthos Island

Photo: Sole

Drosou listed some factors that helped the Greek solar thermal industry to succeed over the years:

- Well-established supply chain: Several collector and tank manufacturers were set up during or after the energy crises in the mid-1970s; national solar thermal industry association EBHE was founded as early as 1979.

- Government support: In the 1980s, the Greek government launched campaigns promoting solar thermal systems and offered incentives, such as a reduced VAT rate and low-interest loans, to drive demand, which resulted in a large number of installations.

- Early adopter of standards and certification: Greece’s industry pioneered efforts to establish and support European Committee CEN TC 312 on solar thermal systems and components. So far, the EBHE-supported CEN TC secretariat has always been headed by experts from Greece. Meanwhile, over 100 Greek products have been Solar Keymark-certified. This corresponds to about 10 % of all active licences in the Solar Keymark product database.

- High home ownership rate: In all, 75 % of flats and homes in Greece are privately owned. A Greek family invests heavily in their own flat, aiming at a high degree of autonomy. This also includes adding hot water lines, which they are hesitant to share with neighbours.

Major export markets on all continents

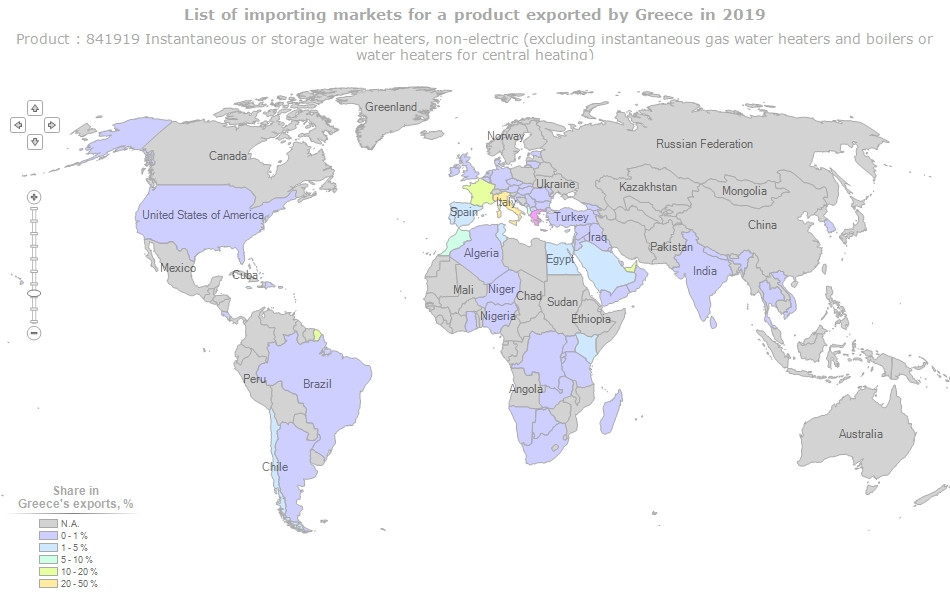

International Trade Centre data recorded under HS code 841919 indicates that Greek manufacturers have a wide distribution network across the world (see the map below). The HS code is used for non-electric instantaneous water heaters and storage water heaters, excluding instantaneous gas water heaters and central heating boilers. Hence, most Greek solar thermal products were exported under this code. The map identifies Italy (21 %) as 2019’s key export market, followed by France, the United Arab Emirates and French Guyana (14 % each). The third category of countries consists of Morocco (7 %) and Albania (6 %), Portugal (5 %), Chile and Egypt (3 %) as well as Saudi Arabia, Kenya and Spain (2 %). Only 1 % each went to Tunisia and the United States.

Target countries for Greek SWH exports under HS code 841919

Source: International Trade Centre

Rising demand post-recession

Drosou’s presentation prompted one webinar participant to ask: “How did the national solar thermal market grow even during the recession?” She replied by saying the recession heightened competition between manufacturers. It not only brought retail prices down but also drove up energy prices. New taxes led to a 120 % spike in the cost of heating oil between 2010 and 2018, and power became more expensive because the government introduced renewable energy and carbon fees. Only natural gas remained nearly affordable, but the national grid supplies fewer than half of all Greek households.

Drosou also mentioned that some governmental support and new business models spurred demand during the recession:

- In 2010, the Energy Efficiency Building Regulations made it mandatory that solar systems be used to meet at least 60 % of hot water demand from all newbuilds.

- A PV generator on the roof is only allowed if a solar water heater system is already in place.

- Since 2010, very low-income families have been able to request a 70 % incentive for their solar water heater from the Energy Saving at Home I and II programmes.

- After online suppliers and large electrical and home appliances chains entered the market, it has become even easier for customers to buy thermosiphon systems.

Organisations mentioned in this article: